Bangladesh (bahng-la-desh, “land of the Bengali people”) – or as we often mispronounce it, Bangladesh (bayng-la-desh,“land of the frog people”) – was home to Amber Goodrum, student success coordinator at Ouachita and former missionary kid, for four years of her childhood. From the age of 5, Goodrum was immersed in a culture radically different from our own: one of Islamic customs, repulsive ferry rides and the saving power of the Gospel.

The land of the frog people

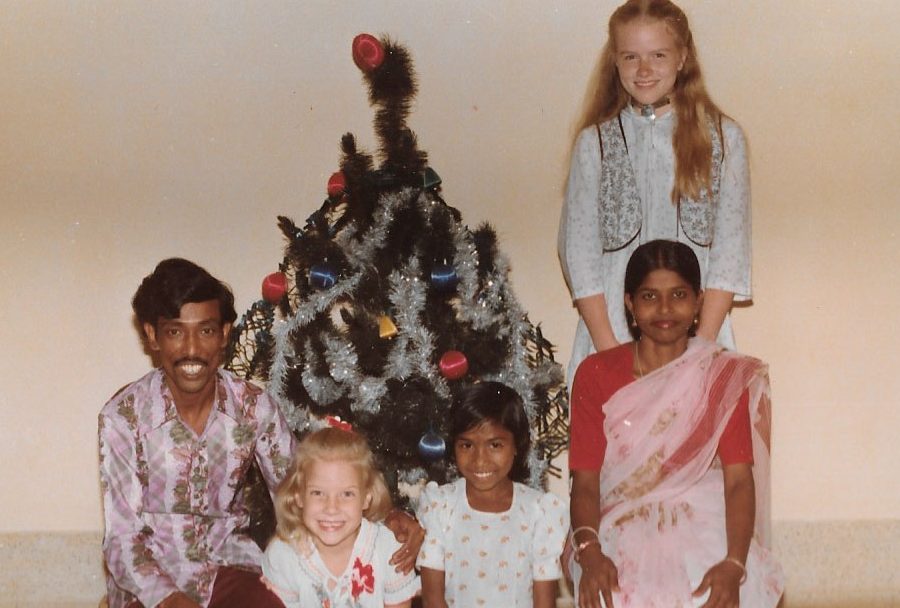

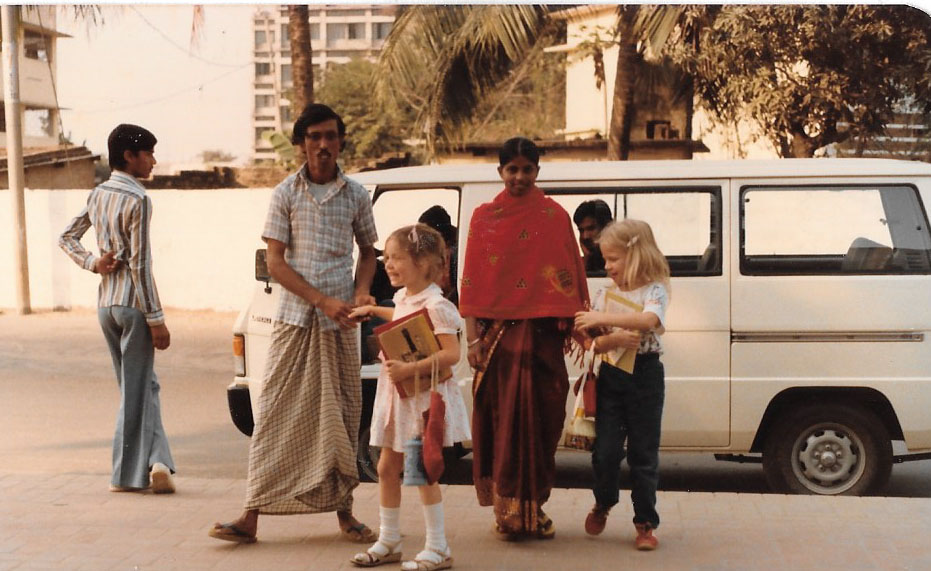

“When we first moved to our village outside of Dhaka (the capital city of Bangladesh), we were the only foreigners that lived there besides a Catholic priest from Europe,” Goodrum said. “My dad was the pastor of the village church, and he did local evangelism and church planning around the area.”

The main concern of missionaries in Bangladesh, however, was relief work. Two major cyclones devastated the country during the family’s stay, resulting in much death and destruction.

In addition to his disaster relief efforts, Goodrum’s dad assisted in tube well drilling for villages that had no clean source of water and started a sewing circle amongst the women in his own village.

“Since it is a Muslim country, most women don’t do much outside of the home. My father wanted them to have a means of hearing the Gospel, while also having the opportunity to make some money for their family,” Goodrum said. “He taught the women how to embroider and then he would sell pieces of their embroidery to people back home in the states and give the money to the women. I believe the sewing circle is still going in that particular village, so that’s pretty exciting.”

Goodrum’s mom was also respectful of the country’s Islamic customs, and therefore would only assist her husband’s work in limited ways, most of the time staying at home to watch Goodrum and her sister. As a way to actively minister to the community, Goodrum’s mom often opened up her home for Christian counseling.

“There were a lot of families or individuals who had not told their family members that they had converted to Christianity, and they were still feeling very oppressed by the Muslim traditions,” Goodrum said. “So they would come to our home and my mom would counsel them and have Bible studies with them.”

When the other moms or families would come over, they would always bring their kids with them. Goodrum remembers fondly the time she spent playing with the other village children and learning the Bengali language from them. Her best memories however, come from the three-hour-long ferry rides she and her family took to get from their village to Dhaka.

“I would always get excited when my parents said it was time to go to Dhaka,” Goodrum said. “My mom and dad say the ferry rides were so sketchy and that the ferry constantly needed to be repaired. My sister said the smells were disgusting because people would just go to the bathroom on the ferry. It’s probably a shock that we’re even alive, but I thought the ferry was great!”

Boarding school in Bangkok

After four short years in Bangladesh, Goodrum’s dad accepted a pastoral position at the English-speaking Calvary Baptist Church in Bangkok, Thailand. He had been offered the job before and turned it down, but with Goodrum’s sister studying at a boarding school in Bangkok at the time, the position presented an opportunity for their family to be reunited.

“It was culture shock moving from Bangladesh to Bangkok because we went from village life to big city life,” Goodrum said.

The second wave of culture shock came when Goodrum enrolled in Bangkok’s international boarding school with her sister, a major departure from her homeschool experience in Bangladesh.

“I never experienced Bengali school or the way the village kids went to school. My experiences in the school environment were all very modernized, very American. However, the boarding school in Thailand was full of all kinds of nationalities and cultures, and that was a really great experience,” Goodrum said.

While there were other missionary families in Thailand, the mission team was much larger than the one in Bangladesh, which, according to Goodrum, made them more difficult to connect with.

“There were only about eight families on the mission field in Bangladesh and we really were a family. But when we moved to Thailand, there were like 70-80 missionary families and it was just very, very different,” Goodrum said. “I still have really good memories of it, but as far as really seeing the work that my dad did as being meaningful mission work, Bangladesh is where my sweet memories are.”

“…what I was created for.”

Around the time that Goodrum was starting high school, the Foreign Mission Board (now IMB) informed her parents it would be too expensive for her to continue her education at the international school in Bangkok. They gave her parents the option of homeschooling her through high school or sending her to a boarding school in Singapore.

“My mom was not going to send another child off to boarding school,” Goodrum said. “They probably could have homeschooled me and I would’ve been fine, but I was the same age that my sister had been when she was homeschooled, and my parents had such a miserable experience with her at that age.”

After a considerable amount prayer and consideration, her parents resigned from the mission board and moved back to the United States, where Goodrum’s sister was studying sociology at Ouachita Baptist University.

Accepting a director of missions position at a local church, Goodrum’s dad moved their family to Missouri, where Goodrum would attend high school. For her, the hardest part about returning to the United States was not adjusting to the modernized culture, but to the southern culture.

“What was so crazy for me was all of the racism that was a part of normal speech and conversation,” Goodrum said. “I was raised to never see color. In Bangladesh, all of my friends were village children and then in Thailand I went to international school, so I could not understand how people talked the way they did and how they negatively viewed other people.”

After high school, Goodrum followed in her sister’s footsteps by attending Ouachita to study education. She began teaching right out of college, and eventually made her way back to her alma mater as an adjunct instructor before being hired in administration.

“Had I not had the experiences that I had overseas, I would not have a broad worldview, I would not be as open to differences in people and I would not have the heart of service that I received from my parents,” Goodrum said. “When people come through my office door, I’m all about it. I don’t care who they are, what color they are or what their economic background is. I graduated 15 years ago, but just now have I realized what I was created for.”

“I do not think you can truly appreciate the world and the different cultures in the world until you see it and live it. There’s something about not being safe that will truly grow your faith and your heart for service and ministry. I think we become better humans if we just step outside our comfort zone and learn about other people and other cultures.”

By: Evan Wheatley, features editor